Georgia’s education chief has some words for Arne Duncan

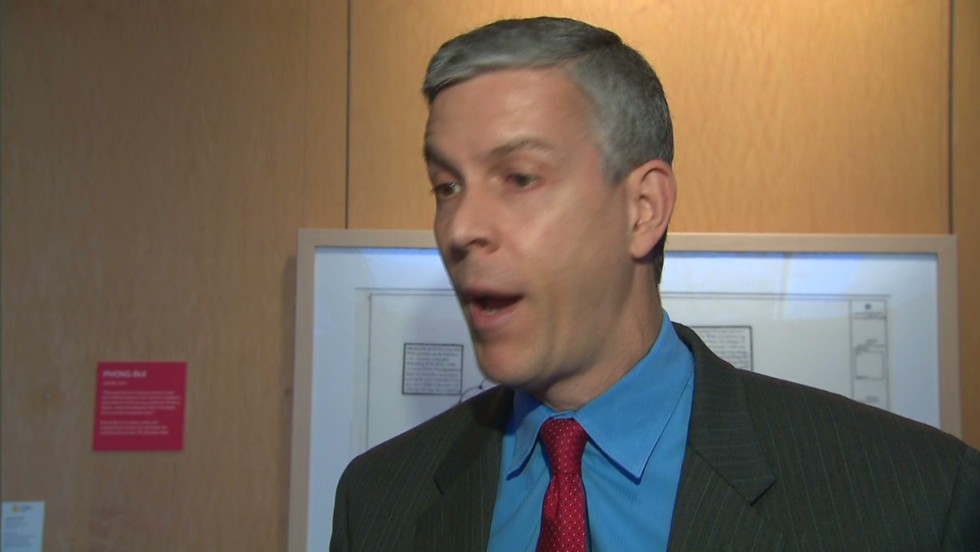

Education Secretary Arne Duncan speaks about the administration’s priorities for education at Seaton Elementary in Washington, Monday, Jan. 12, 2015. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Richard Woods became the State School Superintendent of Georgia last month after spending 22 years in public education in various roles: teacher, teacher mentor, assistant principal, principal, curriculum director, testing coordinator, pre-K director and alternative school director. He is also a former small business owner and was a purchasing agent for a multi-national laser company. This week, Woods wrote a letter to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and sent it, too, to members of Georgia’s delegation in the U.S. Congress and to the House and Senate education committees, which are currently working on legislation to rewrite No Child Left Behind. One of the key issues is whether annual standardized testing, as mandated in NCLB for grades 3-8 and once in high school, will continue in a new education law.

Woods, in his letter to Duncan, urges changes to federal mandates on standardized testing, saying in part:

Our broken model of assessment is too focused on labeling our schools and teachers, and not focused enough on supporting our students. Our current status quo model is forcing our teachers to teach to the test. We need an innovative approach that uses tests to guide instruction, just as scans and tests guide medical professionals. Oftentimes, we hear teachers called professionals because they have the knowledge and skill set to reach the needs of their individual students, yet in our accountability measures we have not supported or given value to diagnostic tools and tests that teachers need to fully utilize that knowledge or those skills. We must find a balance between accountability and responsibility.

Here’s the letter, which was first published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and which I am republishing with permission from Woods.

Dear Secretary Duncan,

With the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) comes an opportunity to address the valid concerns of students, parents, teachers, and communities regarding the quantity and quality of federally mandated standardized tests.

As Georgia’s School Superintendent, I have a constitutional duty to convey those concerns and provide ideas on how to move my state and our nation forward. Georgia recently entered into a $108 million contract to deliver federally mandated standardized tests to our students. That figure does not include the millions of dollars spent to develop and validate test questions and inform the public about the new tests.

This adds to the need for an audit to provide information on the number of tests and loss of instructional time our children endure, as well as a cost/benefit analysis on our current national testing model. As a nation, we have surrendered time, talent, and resources to an emphasis on autopsy-styled assessments, rather than physical-styled assessments. With the reauthorization of ESEA comes an opportunity for a real paradigm shift in the area of assessment.

Instead of a “measure, pressure, and punish” model that sets our students, teachers, and schools up for failure, we need a diagnostic, remediate/accelerate model that personalizes instruction, empowers students, involves parents, and provides real feedback to our teachers.

We need greater emphasis for a federally supported but state-driven formative assessment model that identifies the strengths and weakness of students, coupled with a less intrusive, student-sampled or grade-staggered summative assessment model for the purposes of state-tostate comparisons and world rankings.

Our broken model of assessment is too focused on labeling our schools and teachers, and not focused enough on supporting our students. Our current status quo model is forcing our teachers to teach to the test. We need an innovative approach that uses tests to guide instruction, just as scans and tests guide medical professionals. Oftentimes, we hear teachers called professionals because they have the knowledge and skill set to reach the needs of their individual students, yet in our accountability measures we have not supported or given value to diagnostic tools and tests that teachers need to fully utilize that knowledge or those skills. We must find a balance between accountability and responsibility.

We must give our teachers the tools and trust to be successful or our current path to hyper-accountability will continue to set our students and teachers up for failure. Teachers should not view tests as tools that tie their hands as professionals, but as tools that help them grow in their profession. Students should not view tests as tools that can strengthen barriers to be promoted or to graduate, but as tools that help them overcome those barriers. Schools should not view tests as tools that can doom them to failure, but as tools that serve as a compass pointing them down the path of success.

Testing must be a tool in our toolbox, but we need more rulers and fewer hammers. As Georgia’s School Superintendent, but more importantly as someone with 22 years of Pre-K through twelfth grade experience in education, I strongly urge you to take this moment in history to listen to the concerns of your constituents – parents, teachers, and community members – and reform the federal standardized testing requirements for the betterment of our children. I look forward to working with you to move education forward.

Sent from my iPhone