Meet The Americans Revitalizing Freedom, One Child At A Time

Americans are losing their capacity for self-government. These patriots are doing something about it: opening excellent, America-affirming public schools.

This fall, school started three weeks later than scheduled for the 235 children attending Seven Oaks Classical School near Bloomington, Indiana, thanks to a delayed state loan to fix up their building.

Faculty gave students academic camps from August 15 to September 6 while construction crews added drop ceilings, repainted and repaired walls, installed a new fire alarm system, and brought everything back up to code. Bloomington’s school district had decommissioned Seven Oaks’ building in 2002, so it sat idle until this summer, when Seven Oaks claimed it.

Putting together a new school like this, both mentally and physically, approximates a modern barn-raising. Seven Oaks’ volunteer board of private citizens, who have spent years processing thousands of pages of regulatory grunt work to secure their K-8 school’s charter from the state, also organized community work days to paint, move in furniture, and sundry other mundane but necessary tasks.

Headmaster Steven Shipp went from zero to 235 students in the six months between taking the job and opening the school’s doors. He moved his wife and five children—with a sixth tiny person arriving in March—all the way up from Texas so he could helm the school. Within himself and the 18 teachers he hired he seeks an entrepreneurial, American spirit that rejoices at taking on worthy challenges to better their families, neighbors, and country, he said.

“I’ve told each of them during the hiring process there are two sorts of teachers,” he said. “The kind that wants to step into something settled and carry on the pattern that’s in place, and then there’s the one with the old-fashioned pioneer spirit who wants to step into the wilderness and make something bloom.”

Pioneers in an Academic Desert

For a number of years Shipp resembled the first kind of teacher, whom he described neutrally, akin to a personality type. Yet with this job change—leaving behind safer jobs as a former teacher, assistant principal, then academic director for a network of Texas schools—he seeks to transform himself and his staff into the second.

Many things have influenced his decision, he said, but at the core is something that also motivates Seven Oaks’ board and its midwife, the Barney Charter School Initiative. The initiative from Hillsdale College aims to start quality K-12 public schools across the country using an approximately 20-year-old mechanism called charter schools. Those are public schools local citizens can apply to open and run. They are typically funded at two-thirds the rate of traditional public schools because most don’t receive local property taxes. And they must take every applicant, regardless of family income, race, neighborhood, and so forth.

“I guess I’m old-fashioned,” Shipp said, chuckling. “I really do take seriously the idea of the American founding—you need some critical mass of the citizenry to have enough wisdom and virtue if this republican experiment of ours is going to succeed long-term. I do think this kind of [classical] education has a pretty good track record to that end.”

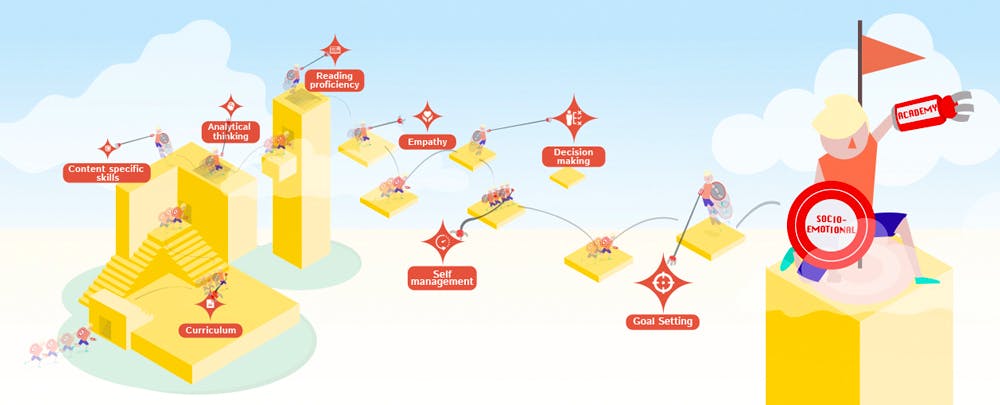

All 16 Barney charter schools follow teaching and curriculum styles last widely seen during America’s great era of common public schools. Nowadays it’s often called “classical education,” but it used to be known as just a good, basic American education. Classes, curriculum topics, and books to read are not handed out cafeteria-style, based on children’s unformed and juvenile desires, but carefully selected to expose children to the best Western civilization has to offer its future. It includes systematic world and American history instruction, explicit phonics, writing, and grammar instruction, mandatory art and music classes, and discipline-based science rather than craft projects and political propaganda.

Barney charters’ K-8 grades use a curriculum plan known as Core Knowledge, which is built on these basic principles of carefully selected core content. Research, most notably by pioneering American public intellectual E.D. Hirsch, has shown this is the most effective way to develop public literacy. That consequently forms citizens who carry the knowledge for and habits of self-government, upon which the American experiment depends.

Barney initiative founder Terrence Moore—an erstwhile Hillsdale professor, current K-12 principal in Atlanta, and founder of one of the nation’s top-ranked public schools, upon which Barney charters are modeled—likes to describe this kind of education as “the kind your grandparents received.” Not only most of today’s school children but most of their parents have been deprived of an academically coherent curriculum like theirs that helps form a common culture and an attendant sense of national unity.

Hirsch’s research shows that the last time a broad majority of Americans had high-quality public schools was approximately the 1950s. The culture wars of the 1960s allowed a minority of radicals to polarize and thus divide the curriculum, as education historian Diane Ravitch has shown, ultimately depriving American generations since of the basic shared knowledge and ideals they need to develop an American identity and habits. These include freedom of speech, respect for private consciences, the equality of every human—ideas our founding documents articulate with great power.

Since progressive education theories gained dominance in the 1960s, American kids’ SAT and other respected test scores tanked, and have never recovered. Never, that is, except inside wealthy, suburban schools and, for everyone else, the few schools providing children the time-tested form of education many now call “classical”—like Seven Oaks.

‘They’re Being Shortchanged, and Something Can Be Done’

Hillsdale’s initiative is a mere six years old, and continues to grow steadily, helping local boards of parents and community volunteers open schools at a rate of between three and five per year. Their biggest obstacles tend to be financial and regulatory, said Phillip Kilgore, the initiative’s director. State chartering boards have rejected school petitions over issues as trivial as the age of math textbooks they plan to use (because addition and multiplication formulas change every five years?).

The parent-directed boards that get the schools running also need to invest thousands of man-hours fulfilling paperwork mandates for this and that, hiring a principal, finding school property and furniture, and so forth. It’s a heavy lift for people with families and day jobs, especially with no assurance the state will approve their proposal. The Barney initiative comes alongside these folks, offering them model charter applications, help finding and hiring principals and teachers and navigating employment law, and teacher training both before the schools open and observations and repeated in-person critiques afterwards.

Hillsdale charters educate something like 4,000 children so far. It’s a drop in the bucket compared to the 54 million school-age children in America. But Kilgore thinks it’s “hubristic” to pretend one initiative can “save the country.” He and his fellow Americans are just trying to do their part.

“We want to awaken the American people to know they’re being shortchanged, and something can be done,” Kilgore said earnestly, pausing to measure his words. “Good education is needed. People are hungry for it, if they’re not getting it. And it needs to be available to everyone, because the republic needs an educated citizenry.”

Tired of Yelling at their TV Screens

He spoke after a summer institute dedicated to introducing new volunteers to the ideas behind the Barney initiative, on Hillsdale’s verdant, humid campus in July. Fifteen people, ranging in age from late twenties to sixties, spent three days immersed in classical education topics and techniques to alternating sounds outside of drill bores for construction and birds twittering in the trees.

‘We could throw our hands up and complain about the state of our country, or we could get our hands dirty and help someone,’ said Faith.

Moore playacted the part of the Federalists and Anti-Federalists of the American Revolution, illustrating ways to engage children in Western civilization’s great ideas. The seminar room’s whiteboards proclaimed: “I will learn the true. I will do the good. I will love the beautiful.” Participants discussed Benjamin Franklin’s efforts to teach himself to write by copying essays from Joseph Addison’s Spectator, during the “golden age of essay writing.”

Faith and Bob Ham had come that day because they were tired of yelling at the politics on their TV screens, Faith said: “We could throw our hands up and complain about the state of our country, or we could get our hands dirty and help someone,” said Faith, an elegant, upright woman with a soft voice.

Across from them sat Courtney Hayes, an African-American first grade teacher in Prince George’s County public schools next to Washington DC. He quit his job in the tech industry in 1997, the last wave of education desperation, to move back into the city from the suburbs and make a difference in poor kids’ lives.

Hayes’ students come to class hungry and missing teeth, he said. Despite his strenuous efforts and many successes at moving up kids who enter school already hopelessly behind, he feels pressure to advance students to make the school district’s state accountability numbers look better, when some kids would do better repeating a grade, he said.

“I can’t retire,” he says. “Those kids need help.” That’s why he showed up at Hillsdale that day. As he left the campus, he and another DC-area teacher made plans to see what they could do to bring a Barney charter to their city. Because every American’s child needs an excellent school if a democratic republic like ours wants a prayer to survive—and they’ve had enough with expecting someone else to fix their neighbors’ problems.

Joy Pullmann is managing editor of The Federalist and author of the forthcoming "The Education Invasion: How Common Core Fights Parents for Control of American Kids," from Encounter Books.